A lot can be told about British opinion and tastes in landscape painting between 1750 and 1850 from the lines of James Thompson’s poem The Castle of Indolence:

‘Whate’re Lorrain light touched with softening hue

Or savage Rosa dashed, or learned Poussin drew’

First of all, and most simply, was the taste for older artists; those which had been around and in the public eye for at least a hundred years or so and therefore had successfully passed the test of time. Another – and equally as obvious, if not more – is a preference for central European landscapes and landscape artists. The lines also hint to interest in the idea of the Classicly Beautiful, which was more linked to the art of Claude, and the Sublime, which was more linked to art of Rosa, with Poussin hanging between both depending on which of his works one looks at. For all of this, the most relevant person to observe would be Joseph Mallord William Turner. Born in 1775 and dying in 1851, Turner lived through the very centre of the period of time this relates to, and was influenced at some point or another by all three artists mentioned in The Castle of Indolence, but most importantly by Claude who became a running feature in Turner’s art throughout the most part of his artistic career.

As I stated earlier, the most obvious idea that can be lifted from the lines is the taste for the landscapes of mainland Europe, mainly influenced by the scenery of Italy – or more specifically, Rome – and Biblical or classical tales. An example is Claude Lorraine’s Landscape with Narcissus and Echo, illustrating the story of a mountain nymph called  Echo who falls unrequitedly in love with Narcissus, a beautiful young man who in turn falls in love with his own reflection and eventually wastes away until only a flower is left in his place. While it shows this tale, it is predominantly an idealised Italian landscape, with Claude’s iconic use of yellow light that initially attracts the viewer’s eyes to the background – where there is a small town, boats resting in a harbour and a castle on a cliff – and way of employing trees and darker tones in the foreground as a mode of framing the landscape. The figures only rest in the bottom right hand corner, staking up very little of the painting. Other examples of classical and biblical narrative from the artists outlined in the poem include Rosa’s River Landscape with Apollo and the Cumean Sibyl and Poussin’s Arcadian Shepherds. This usage of Greek and Roman myths and legends – however marginalised it might be in some of the art, due to the lack of respect for pure landscape painting at the time they were made – may have worked as a catalyst towards the development of Neoclassicism in the mid eighteenth century, having helped found an interest in it, along with the advancement of archaeological discoveries of the time; though this movement initially developed in Europe as opposed to Britain.

Echo who falls unrequitedly in love with Narcissus, a beautiful young man who in turn falls in love with his own reflection and eventually wastes away until only a flower is left in his place. While it shows this tale, it is predominantly an idealised Italian landscape, with Claude’s iconic use of yellow light that initially attracts the viewer’s eyes to the background – where there is a small town, boats resting in a harbour and a castle on a cliff – and way of employing trees and darker tones in the foreground as a mode of framing the landscape. The figures only rest in the bottom right hand corner, staking up very little of the painting. Other examples of classical and biblical narrative from the artists outlined in the poem include Rosa’s River Landscape with Apollo and the Cumean Sibyl and Poussin’s Arcadian Shepherds. This usage of Greek and Roman myths and legends – however marginalised it might be in some of the art, due to the lack of respect for pure landscape painting at the time they were made – may have worked as a catalyst towards the development of Neoclassicism in the mid eighteenth century, having helped found an interest in it, along with the advancement of archaeological discoveries of the time; though this movement initially developed in Europe as opposed to Britain.

Another influence in British taste in landscape, as the poem suggests, is Claude’s use of light. This was especially specific to Turner whose work had a great impact upon it from Claude, often using the same framing effect and, again, the appearance of classical tales. This also inspired him to travel to Italy from 1819 to 1820 and again in 1829 in order to study the scenery that had previously animated Claude’s work. He sought out places he knew from the paintings like the lake Albino and sketched out the key sites that Claude had made familiar to him in order to capture the French artist’s style and so that he could use them or their structure in his paintings after hand. Even in the pieces before he travelled to Italy, one can easily see parallels in Turner and Claude’s art, with some of Turner’s earlier paintings nearly entirely replicating that of Claude. A prime example of this is his Appulia in  Search of Appulus in which the scene is almost identical to Claude’s Landscape with Jacob, Laban and his Daughters. Both show a landscape with a river cutting through it from the left and a long arched bridge stretching across it and reflecting

Search of Appulus in which the scene is almost identical to Claude’s Landscape with Jacob, Laban and his Daughters. Both show a landscape with a river cutting through it from the left and a long arched bridge stretching across it and reflecting  against the water below. On the right of the scene in each, there is a small cluster of buildings, in Claude’s case it’s classical architecture and in Turner’s ruins, adding to the Picturesque effect of his work. The trees that frame the more central landscape are unbelievably similar in shape and structure, along with the placing of the sheep in the left hand corner and cows along the river bank in the centre of the painting. Even the details are exact, down to the colour of the figures’ outfits. There are, of course, many less obviously influenced paintings such as The Rise of the Carthaginian

against the water below. On the right of the scene in each, there is a small cluster of buildings, in Claude’s case it’s classical architecture and in Turner’s ruins, adding to the Picturesque effect of his work. The trees that frame the more central landscape are unbelievably similar in shape and structure, along with the placing of the sheep in the left hand corner and cows along the river bank in the centre of the painting. Even the details are exact, down to the colour of the figures’ outfits. There are, of course, many less obviously influenced paintings such as The Rise of the Carthaginian  Empire which shows a river running between sets of buildings and tells a scene from the story of Dido, the female figure in blue on the left, as she builds her husband’s tomb which appears beside her in the painting. This can be coupled with Claude’s Seaport with the Embarkation of Queen Sheba. Though these paintings aren’t identical like the previous two, the structure in them is very similar with a central beam of yellowy light piercing through dark water and Claude’s work also being bordered by pale buildings and figures, emitting the same sort of atmosphere – however Turners seems marginally darker, with a greater presence of a tree on the right hand side, but this may have been done intentionally to emphasise the situation at hand in his own painting. For these reasons, Turner was often referred to, at the time, as the ‘modern’ or ‘British Claude’.

Empire which shows a river running between sets of buildings and tells a scene from the story of Dido, the female figure in blue on the left, as she builds her husband’s tomb which appears beside her in the painting. This can be coupled with Claude’s Seaport with the Embarkation of Queen Sheba. Though these paintings aren’t identical like the previous two, the structure in them is very similar with a central beam of yellowy light piercing through dark water and Claude’s work also being bordered by pale buildings and figures, emitting the same sort of atmosphere – however Turners seems marginally darker, with a greater presence of a tree on the right hand side, but this may have been done intentionally to emphasise the situation at hand in his own painting. For these reasons, Turner was often referred to, at the time, as the ‘modern’ or ‘British Claude’.

While Claude may have been an inspiration for Turner, he saw him as as much of a rival for his own work as anything, trying to surpass him, remake the Claudian legacy in his own image and further the legitimacy of landscape painting as Claude had done before him. This desire for them to be compared and for Turner to show himself as the superior finally manifested itself in physical form at the end his life when he bequeathed The Rise of the Carthaginian Empire and Sun Rising through Vapour to the National Gallery on the condition they be placed next Claude’s paintings Landscape with the Marriage of Isaac and Rebecca and Seaport with the Embarkation of Queen Sheba.

However, in Turner’s later work, he began to swap his Classic approach for a more Sublime one and his paintings became increasingly vague. While Claude’s influence still reveals itself through the light he uses, depicting “not objects of nature but the medium through which they are seen” and the lingering presence of dark, framing trees and yellow hue, his eye turned further toward the work of Rosa. Described in the poem as ‘savage’, Rosa’s paintings portray the violence of nature, with characters standing beneath looming  cliffs and rocks, ominous, grey skies hanging above and bare, twisted trees punctuating the landscape. This can be seen in his oil painting Rocky Landscape with Huntsman and Warriors, showing four figures all comparatively small to the vast expanses of rock around them. A cloud blankets dark sky above and the gnarled trees frame the bottom of the picture. The atmosphere can also be found in Poussin’s Winter: The Deluge, depicting fierce weather – what appears to be the aftermath of a flood. In the background there is a thin streak of white from what must be moon light lining edge of a cloud, though at a

cliffs and rocks, ominous, grey skies hanging above and bare, twisted trees punctuating the landscape. This can be seen in his oil painting Rocky Landscape with Huntsman and Warriors, showing four figures all comparatively small to the vast expanses of rock around them. A cloud blankets dark sky above and the gnarled trees frame the bottom of the picture. The atmosphere can also be found in Poussin’s Winter: The Deluge, depicting fierce weather – what appears to be the aftermath of a flood. In the background there is a thin streak of white from what must be moon light lining edge of a cloud, though at a  glance looks like a flash of lightning. Both these paintings say something about nature’s raw power, an idea that influenced Turner in his paintings of stormy seas and perhaps to an extent the power of light that exhibits itself in his paintings. The painting of Turner’s that shows this power best is Snow Storm: Steamboat off a Harbour’s Mouth. While it seems to be primarily abstract, with only a few small details indicating the presence of something, the effect is still substantial. The use of swift marks and tones in the shape of the waves and the undefined border between sky and sea offer a glimpse into the brutality of the storm. The darker lines draw the eye away from the centre of the painting where a bright white light sits, that which initially attracts the viewer’s gaze, and to the plain of greys. As in Rosa and Poussin’s work, the pallet is dark and limited adding to the sombre atmosphere that the painting emits. In order to capture the pure ferocity of being out in a storm, Turner famously had himself tied to mast of a boat and left there for hours, founding the painting on the basis of experience.

glance looks like a flash of lightning. Both these paintings say something about nature’s raw power, an idea that influenced Turner in his paintings of stormy seas and perhaps to an extent the power of light that exhibits itself in his paintings. The painting of Turner’s that shows this power best is Snow Storm: Steamboat off a Harbour’s Mouth. While it seems to be primarily abstract, with only a few small details indicating the presence of something, the effect is still substantial. The use of swift marks and tones in the shape of the waves and the undefined border between sky and sea offer a glimpse into the brutality of the storm. The darker lines draw the eye away from the centre of the painting where a bright white light sits, that which initially attracts the viewer’s gaze, and to the plain of greys. As in Rosa and Poussin’s work, the pallet is dark and limited adding to the sombre atmosphere that the painting emits. In order to capture the pure ferocity of being out in a storm, Turner famously had himself tied to mast of a boat and left there for hours, founding the painting on the basis of experience.

Unfortunately, despite Turner’s own popularity with Ruskin because his work was deemed more true to nature than the old masters, Claude, Poussin and Rosa’s landscapes began fall into the background in Britain in the late 1840s and early 1850’s due to the rise of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, fronted by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Their principles in making art were based on Ruskin’s ideas after discovering his book Modern Painters. Expressing true nature for Ruskin meant recording it in precise detail and  with the highest degree of finish. The Pre-Raphaelites tried to replicate this by painting outdoors in natural daylight and also with clear, bright colours on a white backdrop. Clear differences between Pre-Raphaelite landscapes and Claudian landscapes can be easily seen if only one compares them. For instance, looking at A Study in March otherwise known as In Early Spring by John William Inchbold – a follower of Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites – there is not a single hint of the old ways to it. The central focus belongs to foreground, not the distant background, which has been depicted in intense detail showing the flaking bark on an old tree and hundreds of twisting branches; even grass and dirt on the ground has been portrayed with minute precision. As for the scene behind it, where Claude or Poussin, might’ve had a landscape that stretches until the horizon or some kind of mountainscape, Inchbold’s stops rather abruptly with the appearance of the brow of a hill. Even those with further stretches of landscape and, like the old masters, narrative as well, such as Frank Dicksee’s Chivalry still don’t evoke the same effect. While Claude used trees to frame his landscapes and make certain parts stand out and Poussin’s more centrally narrative works have at least a small window to one behind one character or another’s shoulder or off to the side, the trees in Chivalry shroud the distant landscape, if anything, so only the slightest hint can be seen behind it. Much like a Study in March, the viewer’s eye is centred on the foreground that, again, has been scrupulously painted by the artist, down to the details in the closest leaves and the worn appearance of the tree to which the woman is tied.

with the highest degree of finish. The Pre-Raphaelites tried to replicate this by painting outdoors in natural daylight and also with clear, bright colours on a white backdrop. Clear differences between Pre-Raphaelite landscapes and Claudian landscapes can be easily seen if only one compares them. For instance, looking at A Study in March otherwise known as In Early Spring by John William Inchbold – a follower of Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites – there is not a single hint of the old ways to it. The central focus belongs to foreground, not the distant background, which has been depicted in intense detail showing the flaking bark on an old tree and hundreds of twisting branches; even grass and dirt on the ground has been portrayed with minute precision. As for the scene behind it, where Claude or Poussin, might’ve had a landscape that stretches until the horizon or some kind of mountainscape, Inchbold’s stops rather abruptly with the appearance of the brow of a hill. Even those with further stretches of landscape and, like the old masters, narrative as well, such as Frank Dicksee’s Chivalry still don’t evoke the same effect. While Claude used trees to frame his landscapes and make certain parts stand out and Poussin’s more centrally narrative works have at least a small window to one behind one character or another’s shoulder or off to the side, the trees in Chivalry shroud the distant landscape, if anything, so only the slightest hint can be seen behind it. Much like a Study in March, the viewer’s eye is centred on the foreground that, again, has been scrupulously painted by the artist, down to the details in the closest leaves and the worn appearance of the tree to which the woman is tied.

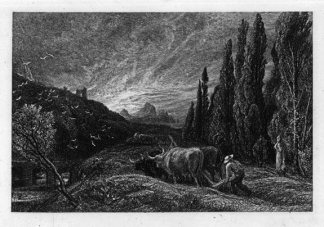

Though Samuel Palmer’s work came a little later, and doesn’t quite fall into the bracket, there still an obvious influence from Claude in his prints and paintings after around 1860 – one of the most notable being A Dream in Apennine. As the title suggests, the painting is set in Italy, hinting further to the influence of Lorrain. There is a small group of figures in the foreground, a far stretching landscape that fades to blue at the horizon and the use of  trees and darker tones to frame the scene: all iconic characteristics of Claudian landscapes. This structure is also replicated in many of his later prints such as The Early Ploughman and The Lonely Tower, showing that the old masters’ legacy managed to live on in some form – even while Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites were at work and discrediting it.

trees and darker tones to frame the scene: all iconic characteristics of Claudian landscapes. This structure is also replicated in many of his later prints such as The Early Ploughman and The Lonely Tower, showing that the old masters’ legacy managed to live on in some form – even while Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites were at work and discrediting it.